By Joel Dresang

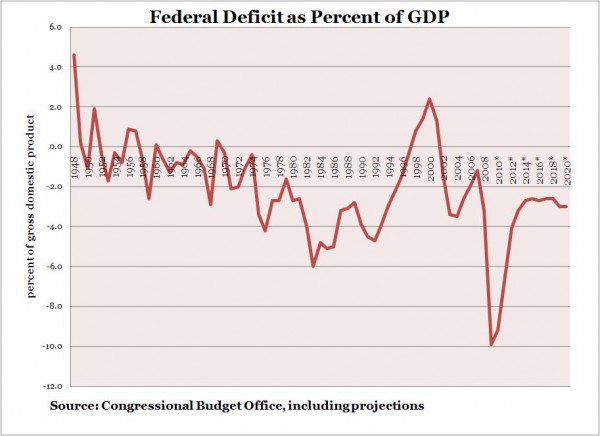

The U.S. federal government reached a record budget deficit in 2009: $1.4 trillion –about one-tenth of the nation’s economic output for the year.

No one can deny that’s a deep hole to climb out of. Even relative to the size of the economy, it’s the biggest deficit as far back as the end of World War II, eclipsing the previous mark set in 1983, according to data from the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office.

“I think everyone is rightfully concerned about the deficits,” says Bob Landaas, president of Landaas & Company. “As a money manager, I care about the value of the U.S. dollar, and because these deficits are going to remain stubbornly high over the next ten years, the dollar has nowhere to go but down.”

A weak dollar can put a damper on foreign confidence in U.S. investments, requiring higher interest rates to attract investors and thus making credit more expensive for the U.S. consumers and businesses whose spending drives economic growth.

According to economic theory, deficits can help prime the pump during economic dry spells by using public funds to encourage the private spending through which prosperity springs. The tricky part is determining the optimal timing, targets and amount of government spending to get the economy – as well as government revenue – flowing again.

Although concerned about the deficit in the long run, Bob says he sees it as no imminent threat to America or American investors. He notes that although deficits are a longstanding problem, they have ballooned recently through a combination of extraordinary circumstances, including an economic downturn through which tax revenue plummeted and government spending on bailouts and stimulus initiatives soared.

“These deficits aren’t going to go away anytime soon, but they’re not new news,” Bob says. “They’re the result of the Iraq war, the Afghanistan war, the collapse in the economy that began in early ’08 and the tax cuts that were enacted in 2003 without Congress making necessary spending reductions. I’m all in favor of tax cuts, but you’ve got to spend less if you’re going to tax less.”

Although some political pundits have sounded alarmist warnings around the immediate impact of the new record deficit, Bob is among economists taking a longer, calmer view of the situation.

A couple of signs that the deficit isn’t a near-term threat, Bob notes, is that the dollar has been rising in value since late 2009 and interest rates on Treasury securities have remained historically low.

“The big money doesn’t think inflation is going to be an issue because of these deficits,” Bob says. “The big money is saying the economy is pretty weak, that interest rates are stable or even declining recently because of the weakness of the economy.”

In fact, core inflation – which takes out the volatile food and energy categories – actually fell in January, the first time that has happened since 1982. Through April, the 12-month core inflation rate of 0.9% was the lowest since January 1966.

Though she has warned against deficits her whole career, Janet Yellen, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, has said that the current deficit poses no inflation threat.

“In the short run, federal deficits have cushioned the blow from the financial crisis and recession,” Yellen said in a speech in February at the University of San Diego. “As far as inflation is concerned, there’s no evidence that big government deficits cause high inflation in advanced economies with independent central banks, such as the Fed.”

Still, Bob says, current domestic budget problems underscore the need to include global assets in a broadly diversified investment portfolio.

“It speaks volumes to how we ought to be investing money, to favor international investments to get away from U.S. dollars,” Bob says. “But it also tells us that long-term – get ready for this – taxes are going to gradually go up. They have to, to try to reduce the deficits. And entitlement programs have to go down.”

Economic growth will help close some of the gap as revenues increase and the need for stimulus subsides. The Congressional Budget Office has projected that within a couple of years, federal deficits as a share of economic output will be back to where they were around 2005.

“Long-term,” Bob says, “I think we’ll be able to get our arms around the issue.”

Joel Dresang is vice president of communications for Landaas & Company.

initially posted May 1, 2010